By Abujah Racheal

Mr Babagana Garuba, a resident of Waru community in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) did not know he had hepatitis, even though he had been to the hospital over and over again each time his eyes “turned yellow.”

Garuba, a 69-year-old retired civil servant, said that the doctors would dismiss it as typhoid and only prescribe some medication, including eye drops.

Eight years after the symptoms started, he has now been diagnosed with liver cancer caused by the infection.

“Long before I received my diagnosis, I was not aware of such disease as hepatitis.

“Before I retired from service around 2015, my wife battled cancer until her death, and unfortunately, I must have picked up hepatitis during one of her many hospitals stays.

“For the first five years that followed this time, I would develop increasingly severe health complications which had drastic impact on my quality of life.

“I went from doctor to doctor, hospital to hospital, blood test after blood test, only to end up right back at the start, frustrated and confused with no answer in sight,” he said.

He said that the symptoms he experienced leading up to his diagnosis included, yellowing eyes, extreme fatigue “like falling asleep midday and even while driving”, insomnia and rapid weight loss.

“I also experienced food allergies, memory loss, brain fog, stiff joints and yellowing skin,” he said.

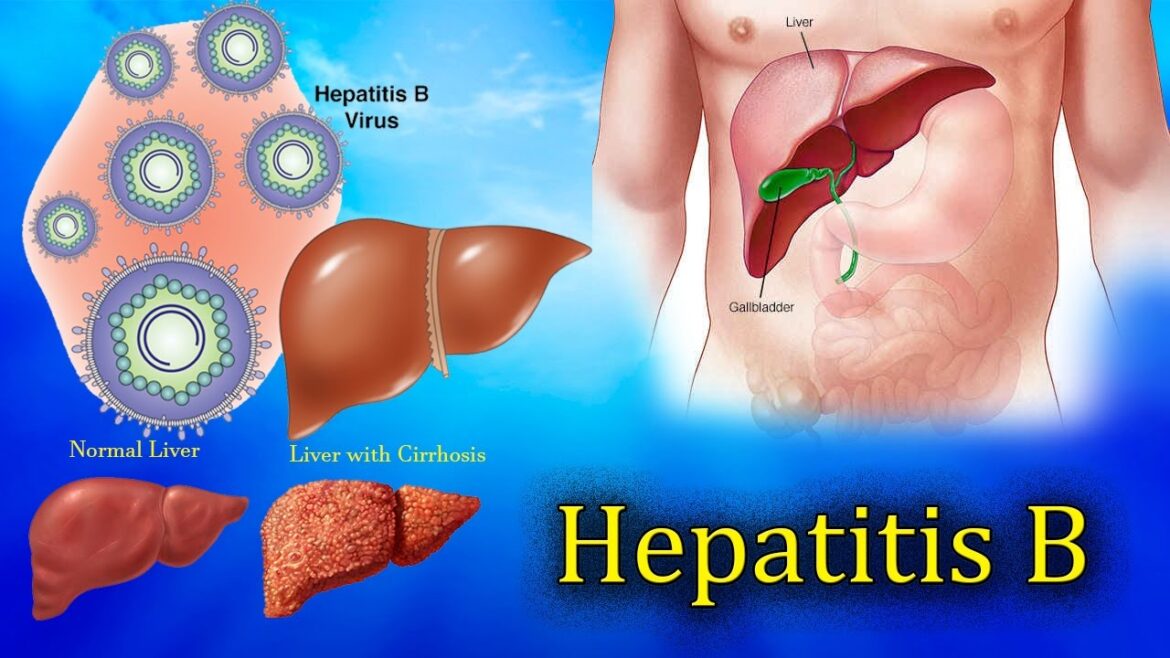

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), hepatitis is the inflammation of the liver. The five most common viral hepatitis are A, B, C, D, and E. Recently, the hepatitis G virus was discovered.

Hepatitis A and E are transmitted through contaminated food, water, poor hygiene and close contact with carriers of the virus.

Hepatitis B, C and D are transmitted through blood, sexual intercourse, bodily fluids, kissing, sharing syringes and blades, and touching wounds of infected persons.

Hepatitis G’s route of transmission is same with that of B, C and D.

Studies have revealed that hepatitis A and E are acute; lasts for a short time – less than six months and hepatitis B, C, D and G may progress to chronicity; more than six months.

Viral hepatitis starts from absence of symptoms (asymptomatic)) to mild or moderate features such as jaundice-; yellowish discoloration of the skin and eyes, poor appetite, malaise and progressing to a chronic liver failure.

Hepatitis remains a disease of public health importance and its mortality remains alarming, due to limited global progress in addressing the scourge.

The scourge arising from hepatitis complications become worrisome to Nigerians, and it requires compelling measures towards its alleviation.

Majority of those who have viral hepatitis do not know it, and the vast majority of those who are sick are not getting diagnosed and treated until it becomes too late.

Some people get the virus from their mothers at birth. Some get it through sexual contact, or because health care providers do not properly screen blood transfusions or sterilise equipment.

Shared needles, sharp objects at home, and traditional practices such as circumcision, tattooing, and scarification also spread the disease.

Health experts have raised alarm that Nigeria contributes significantly to the burden of chronic viral hepatitis infection globally with the prevalence of 11 per cent and 2.2 per cent for viral hepatitis B and C respectively.

This has resulted to above 20 million Nigerians living with viral hepatitis B or C in a population of 177 million individuals.

They may not be aware and are at the risk of developing chronic complications of liver cirrhosis and primary liver cell cancers.

Most worrisome is the risk of transmitting the infection to other unsuspecting members of the community.

The experts said the increasing cases and related deaths due to the disease were because it was not well funded.

They said that there was a lack of education and public health programmes supporting elimination efforts.

Despite presenting a major public health challenge, viral hepatitis has been historically marginalised as a health and development priority.

However, in 2015, the United Nations adopted a resolution calling for specific action to combat viral hepatitis as part of its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

It was followed by the publication of the WHO’s first global strategy on viral hepatitis in 2016.

The large population and relatively high prevalence rates of hepatitis B and C suggest that the nation should be considered a key country for hepatitis elimination efforts.

In response to high prevalence rates and alignment with the global effort toward elimination, the Federal Ministry of Health, developed the National Viral Hepatitis Strategic Plan 2016 to 2020.

The plan mapped out actions to put the country on the path of hepatitis elimination.

The National guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of viral hepatitis B and C were also developed and published in 2016.

It centred on firmly establishing the management of viral hepatitis as part of Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

Although there is a paucity of data on modes of viral hepatitis transmission within Nigeria, local intelligence suggests that there are some particularly relevant modes of transmission.

They include mother-to-child transmission, healthcare-related transmission due to poor infection control and traditional cultural practices, including scarification, female genital mutilation, male circumcision, and “uvulectomy”.

However, whilst this political will and strategic direction are promising, there remain substantial challenges to the realisation of these plans and the attainment of elimination goals in Nigeria.

Although there have been efforts to work towards UHC in the country, the health system has limited funding, and there is a need for coordination between the levels of government.

A study was recently conducted by conversation.com, a meta-analysis consisting of studies published between 2010 and 2019, to determine HBV prevalence.

There were 47 studies and a sample size of 21,702 people. The prevalence rate of 9.5 per cent that emerged from the analysis means that the country meets the WHO’s criteria for high endemicity.

The study found differences in infection levels across different geo-political zones and settings.

Higher rates of HBV infection were found in the North-West geo-political zone (12.1per cent), compared with the South-East (5.9 per cent).

Infection rates in rural areas were also much higher (10.7 per cent) than those in the cities (8.2 per cent).

The study could not provide the reasons for this but suggested that it may be due to inequalities in access to health services, and due to differences between culturally diverse groups.

Dr Paul Oboro, a hepatologist, said for the country to be on course to the elimination targets, it must improve access to affordable diagnosis and care for its population.

“People living with hepatitis B virus (HBV). should not have to wait for care until their infection becomes chronic and liver disease reaches an advanced stage.

“HBV diagnostics need to be affordable and accessible now, so people can be linked to care promptly.

“Ensuring high uptake of the vaccine at birth for babies is crucial to preventing new infections. In Nigeria, the current coverage for HBV vaccination is 57 per cent and offers room for improvement,” she explained.

Oboro said that other measures, such as robust pre-conception screening, and the implementation of “test and treat” interventions at low cost for infected couples, were important to prevent mother-to-child transmission of infection.

The expert said that stigma and discrimination were notable barriers that prevented Nigerians from accessing health services, which can delay diagnosis and care.

“Marginalising populations who are vulnerable to HBV, such as people who inject drugs, often leads to their exclusion from testing and clinical care.

“Hepatitis B elimination will only be possible if the Federal Government will ensure no one is left behind,’” she said.

Dr Aminu Aliyu, consultant gastroenterologist at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, advised healthcare providers to discuss options for the management of hepatitis and the side effects of drugs with their patients.

Aliyu observed that treatment of Hepatitis B could be life-long, which requires healthcare providers to discuss options of management with their patients.

“The clinical goal of treatment is to improve the quality of life of affected patients,” he added.

The hepatologist explained that transmission of viral infections was the most common cause of hepatitis and could happen vertically or horizontally.

According to him, vertical transmission occurs between mother and child during pregnancy or labour, while horizontal transmission can occur from child to child at schools especially, where there is a cut in the skin or mucosal surface.

He further stated that unprotected sexual activities with an infected partner were another major source of contracting the disease.

“Even though hepatitis is common all over the country, it is prevalent in the North-Central geopolitical zone, especially Nasarawa State,” he disclosed.

Aliyu also advised that patients would need to ensure that all their immediate family members were screened for the disease.

He encouraged abstinence from ingestion of alcohol, smoking and herbal concoctions as a preventive measure.

“Immunity against the disease can either come naturally or via vaccinations,” he said.

Aliyu also canvassed for improved healthcare education, sustained vaccination exercise, proper screening, faithfulness to sex partners and robust contact tracing as some of the veritable measures that would lead to a drastic reduction of infection in the country.

Dr Ibecheole Julius, Executive Director, Elohim Foundation, said that the country needed greater investment in tackling viral hepatitis.

Julius, who is also the National Secretary of, the Civil Society Network on Hepatitis, Nigeria (CiSNH, N), said that the major hurdle to achieving hepatitis elimination in the country was the lack of finances to support the hepatitis programme.

“None of the major global donors are committed to investing in the fight against hepatitis. It will be very difficult for low and middle-income countries to fund their hepatitis control programme.

“Hepatitis elimination needs strong financial and political commitment, support from civil societies, and support from pharmaceutical and medical companies around the globe.

“The Global Fund helps to fight HIV, TB and malaria, but no such mechanism for viral hepatitis. Ideally, the remit of the global fund could expand, but without it, other organisations can help.

“In particular, UNITAID, a global health initiative, which has a mandate for improving access to diagnostics and treatment in low-income settings such as Nigeria.,” he said.

He said that unless something drastic was done, the country and most of Africa stood the risk of missing the SDGs Goal 3.3 and the WHO Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis Elimination target for 2030.

“Nigeria, with its vast mineral, natural resources, and human capital, has what it takes to eliminate viral hepatitis by 2030.

“But what it lacks is the strong political will and financial commitment by governments at all levels to finance an elimination strategy,” he said.

Meanwhile, World Hepatitis Day is invariably marked annually, precisely on July 28, the world shall commemorate the 2022 edition of the global programme.

The World Hepatitis Day is one of the eight official global public health campaigns being marked by the WHO.

The first global World Hepatitis Day was marked on May 19, 2008.

The date of the event was later changed to July 28 each year by the assembly, in honour of the birthday of Nobel Laureate Baruch Samuel Blumberg – the man who discovered the Hepatitis B virus.

The health sector and its partner must be aptly improved by providing all the tech-driven measures required to tackle the prevalent scourge of hepatitis in the country. The needed technicalities ought to be properly deployed and sustained as the journey progresses towards the elimination of Hepatitis in the country come 2030.

(NANFeatures)